Although you can certainly plant too

early even in a cold frame, it does give you, and the seed, a chance to get an

earlier start than open ground planting might allow.

Of course, cold frames are not just spring tools, though that’s

their busy time. I use them as well in the fall, and some years all summer long.

In milder climates winter is their season. With the varying and unpredictable

weather we have, they are a tool to reach for any time of the year.

In our short growing season of the upper Midwest, cold frames

are more than just an interesting tool, they are a necessity in my quest to grow

most of the food we eat. They ease the "frost stress" part of

gardening, which makes this gardener a happier camper. And they allow for more

in-season-out-of-the-garden eating, which makes for healthier, happier, and

richer homesteaders. Besides which, they are easy and inexpensive. I wouldn’t

want to garden without them.

MAKING THE COLD FRAME -- Cold

frames can be fancy or simple. Like many of the tools on our homestead, ours are

straightforward and functional, using recycled and scrap materials. Our current

frames are of two designs based on the windows used for the tops. I prefer glass

for glazing over plastic, not only because of the non-disposable aspect

(important to me) but because they are heavier and not as apt to blow off in a

wind. Even with that weight, I’ve had a few go flying in a good gust, but it

is rare and in over twenty years have only had two break. It’s nice to make

use of something destined for the landfill rather than buy new something that

will have to be landfilled and replaced many, many times over the life of the

cold frame.

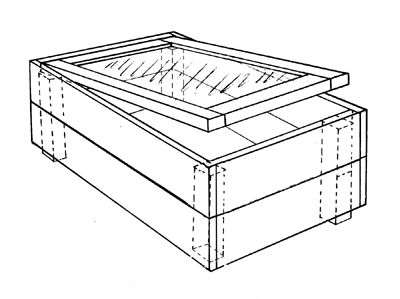

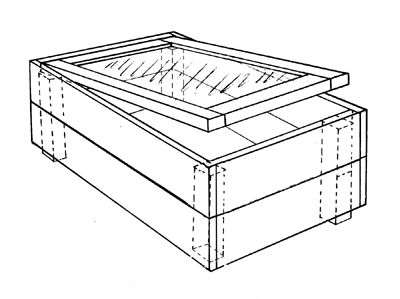

INSET FRAMES: We made our first cold frame windows ourselves because we had

extra glass left over from building our house. Window glass is also readily

available in old windows whose frames are past use (or that had lead based paint

which you don’t want in your garden). Just remove the frames and use the

glass. Or look for good, used framed windows. Our homemade window frames are of

simple, overlapped corners design, made of pine.

INSET FRAMES: We made our first cold frame windows ourselves because we had

extra glass left over from building our house. Window glass is also readily

available in old windows whose frames are past use (or that had lead based paint

which you don’t want in your garden). Just remove the frames and use the

glass. Or look for good, used framed windows. Our homemade window frames are of

simple, overlapped corners design, made of pine.

Whether you make your own or use recycled windows, scrape off

any loose paint and caulk around the glass with silicone sealant. You can use

any non-toxic oil finish for the wood (remember, this will be in your garden).

An inexpensive and easy solution we’ve used is two parts raw linseed oil to

one part turpentine. I’ve also used a more expensive commercial pine-tar based

product, thinned with raw linseed oil to make it go farther (it is a black

finish). Boiled linseed oil would be fine, too. Or just leave the wood

unfinished.

You could set your windows on a plain wood box for a cold

frame, and I’ve done that. It works, but if your window frame isn’t flat on

the bottom, there will be a too-generous air leak on two edges. And when you

tilt the window up for air circulation (which you will be doing quite often), it

has a tendency to slip right off the back of the box. Our solution for this set

of windows was to build the frame box large enough to set the windows down in.

The

size of your box will be determined by the size of your windows. Add a half inch

to the measurement of the window (both length and width) and that will be the

inside dimensions of your box. The extra half inch (1/4" on each side) is

important because your box is likely to swell and warp some in the rain and sun,

preventing you from opening the window if it is too tight. It does give space

for some air leakage, but I’ve not found that to be a problem. I rather prefer

the design because of that little bit of air circulation.

Use whatever wood you have or is available. Our first boxes

were of poplar -- probably one of the least recommended woods for outdoor use.

But it was what we had, and those boxes lasted for many years (long enough I can’t

remember just when we first made them). When they finally did rot enough that

they were falling apart at the corners, we rebuilt out of salvaged wood from our

torn-down chicken coup -- a combination of poplar, pine, and cedar -- much of

which was, itself, salvaged from some other project! As with the window frames,

just make sure the wood doesn’t have a toxic finish you don’t want in your

garden.

Cut your boards to size, then nail or screw them together at

the corners to form a box. We’ve found deck or drywall screws to work well.

Then make 2x2" blocks for the corners. Two of them, installed in opposite

corners, should be as long as the width of your boards (the height of the cold

frame box). The other two, installed in the other opposite corners, should be

the width minus one inch. Install (with appropriate sized screws) the long ones

so they stick down one inch, the other two so they are even with the bottom of

the box. This way all of the corner pieces are one inch down from the top and

this is what the window rests on, inside of the box. In both securing the boards

to each other and installing the inside corner pieces, it helps to first drill

holes for the screws. The corner pieces not only hold up the window, they add to

the rigidity of the box which is necessary since you’ll be moving the boxes a

lot over the years.

So what about the two corner pieces that stick down? Well,

one box is seldom tall enough for the cold frame as the plants grow so you will

soon want to add one (or more) boxes, one on top of each other. These lowered

corner pieces fit into the box below and help stabilize the stack, keeping you

from pulling the top box off as you open and close the windows. It’s not

necessary, but it helps a lot.

The last refinement is to add some type of handles to your

windows so you can easily open them. Ours are a wide variety of salvaged and

homemade designs. Anything that will allow you to lift the window up for

propping it open will do. Since my frames are rectangular and used sometimes

across and sometimes lengthwise on a bed, I have handles on two adjacent sides

of the window.

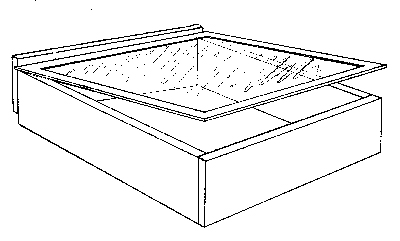

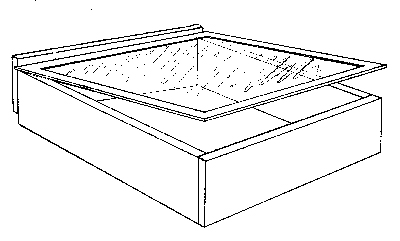

TOP SET FRAMES -- Another simple design is the top-set frame, but with a slight

enhancement to keep the window from slipping off the back. We came up with this

second cold frame design when a friend gave us a batch of old aluminum clad

windows he’d replaced on a job. They were pretty flimsy compared to our

wood-framed windows, and not easy to attach a handle, so we made a box they

could sit on. This design can, of course, be used for any window that is flat on

the bottom, whether metal or wood framed.

TOP SET FRAMES -- Another simple design is the top-set frame, but with a slight

enhancement to keep the window from slipping off the back. We came up with this

second cold frame design when a friend gave us a batch of old aluminum clad

windows he’d replaced on a job. They were pretty flimsy compared to our

wood-framed windows, and not easy to attach a handle, so we made a box they

could sit on. This design can, of course, be used for any window that is flat on

the bottom, whether metal or wood framed.

We had also been given some pallets which we tore apart to

use for the boxes. These boxes are slightly smaller than the dimensions of the

window with the back board (which should go entirely across the back) sticking

up 1/2" to 3/4". The window then sits on top of the front and sides of

the box, snug against the raised back board. This prevents the window from

sliding off the back when propped open, and gives some stability when the boxes

are stacked as the raised board of one snugs into the raised board of the other.

With the aluminum windows, we sized the boxes so the window would stick out over

the front edge which allows us to easily lift the window.

These boxes also have 1 1/2" to 2" corner pieces to

sturdy up the box, particularly needed since our pallet lumber was only

1/2" thick. These salvaged cold frame boxes are pretty fancy with wood of

cherry, maple, and oak. They definitely weigh more than the poplar and pine

ones!

USING THE COLD FRAMES -- The

biggest danger of using cold frames is forgetting to open the windows on a sunny

day. Plants will be damaged more by over heating than cold. So a prop is an

important part of the system. I’ve found a 6" length of 2x4 to be a good

prop giving you three easy options for how far you want the window open --

2", 4", or 6". Generally my cold frames are set up to open from

the south, but if there is a strong wind out of the south, I will prop them open

on the north to keep a gust from flipping the window off. Since my frames are

set flat on the garden beds, there is really no front or back, so they are quite

flexible.

On a warm, sunny day the windows can be simply lifted up and

slid over the back edge of the boxes (or to one side), depending on what other

plants are nearby. If you are going to be gone and it is too cold to leave the

windows open, cover the cold frame with a blanket or rug. It is better to have

the plants in the dark for a day or two that have them freeze or cook.

MINI-GREENHOUSE -- If you don’t

have a greenhouse (or even if you do), you can make a large cold frame to do the

job of starting seedlings. For many years we had a five window long permanent

cold frame in the garden made of discarded windows with back and front walls of

used unmortared cement blocks. The back was taller than the front and the sides

were made of scrap boards. We also put scrap boards on top of the cement blocks

nailed to blocks of wood wedged into the blocks to make a nicer top for the

windows to rest on. Into this large garden cold frame, I moved my

windowsill-started plants as soon as it was warm enough. I also started many

crops such as the coles and cucumbers directly into the cold frame dirt,

transplanting later into the garden. For squash seedlings it was great as you

could use a shovel to transplant and so avoid the transplant shock usually

associated with the cucurbits.

We now have a greenhouse and that does do a better job,

particularly with the warm weather crops such as tomatoes and peppers. But a

large, permanent cold-frame can perform surprisingly well, either as a

substitute or as a supplement to the greenhouse. The large area is warmer than

individual cold frames which the early plants appreciate.

CROPS IN THE COLD-FRAME -- Once you have a few cold frames, you’ll find many

uses for them throughout your garden. You will soon be scrounging up materials

to make more. In the late-summer and fall I start lettuce seedlings in a cold

frame box in the garden. As the weather gets cold and frosts and freezes arrive,

I add the window to protect them, propping it open on warm days. As the cold

settles in, half of the seedlings get transplanted to the greenhouse for late

fall and winter eating, the others continue to grow in the cold frame in the

garden. As the freezes end our regular lettuce crop, we eat the cold frame

protected plants until winter and deep snow arrives and our harvesting turns

inside to the greenhouse (where the plants are, hopefully, well along and

producing). In a milder climate this could continue throughout the winter, and

for other crops.

CROPS IN THE COLD-FRAME -- Once you have a few cold frames, you’ll find many

uses for them throughout your garden. You will soon be scrounging up materials

to make more. In the late-summer and fall I start lettuce seedlings in a cold

frame box in the garden. As the weather gets cold and frosts and freezes arrive,

I add the window to protect them, propping it open on warm days. As the cold

settles in, half of the seedlings get transplanted to the greenhouse for late

fall and winter eating, the others continue to grow in the cold frame in the

garden. As the freezes end our regular lettuce crop, we eat the cold frame

protected plants until winter and deep snow arrives and our harvesting turns

inside to the greenhouse (where the plants are, hopefully, well along and

producing). In a milder climate this could continue throughout the winter, and

for other crops.

Spring is when the entire troupe of

cold frames end up out in the garden, some going from one crop to another,

others sticking with their initial inhabitants until the weather warms and

stabilizes. Lettuce and greens are the first -- some to be planted in a cold

frame, others transplanted from the greenhouse. These first outside-grown early

greens are appreciated as no others can be. Sometimes I try some extra early

carrots as well, though they don’t do as well as those planted when the

weather is more suitable.

As the weather warms, I set out frames to

start cucumber and squash seed in, planting directly into the ground where they

will grow. Later the greenhouse tomato and peppers seedlings are transplanted

into more frames. As they grow, frames are stacked on to keep up. Hopefully, the

weather warms up before I run out of frames. The early lettuce and greens are

sturdy enough by then to have their frames removed and they can be used

elsewhere.

In a good year (thankfully most years), as summer arrives and frosts abate, the

cold frames are removed from all of the plants. Four of the windows go on the

solar food dryer, while the rest are stored in the shed until needed in the

fall. The boxes are stacked out of the way not too far from the garden. If you

stack them up off the ground, kitty-corner to one another in the stack, they

will dry better and last longer. I’ve found old tires to be a good base, as

are used cement blocks.

In a good year (thankfully most years), as summer arrives and frosts abate, the

cold frames are removed from all of the plants. Four of the windows go on the

solar food dryer, while the rest are stored in the shed until needed in the

fall. The boxes are stacked out of the way not too far from the garden. If you

stack them up off the ground, kitty-corner to one another in the stack, they

will dry better and last longer. I’ve found old tires to be a good base, as

are used cement blocks.

There are those years, however, that some of the frames never

leave the garden. Those are the cold, cloudy summers that make us worry if we

will get even one ripe tomato to eat, let alone enough to can. These are the

times that we really appreciate the cool weather cole and root crops as we

continue to stack cold frames on the pepper plants as they grow, snug and warm

in their protective boxes, producing in spite of the weather. Cold season

gardeners often manage to grow melons and watermelons this way as well, and the

smaller varieties of tomato plants, too. Larger plants usually soon outgrow

their cold frames and take their chances with the weather with blankets to cover

them on frosty nights.

If you’ve spaced your plants right, you can replace the

cold frames in the fall over the full grown plants to get them through those

early frosts, and extend the harvest just a few more weeks. There is some aspect

of game and some of challenge, along with fun and just plain gathering for food

in gardening. No matter which, cold frames can help the gardener out, and make

the gardening life a little easier. If you take your plants’ natural needs

into consideration, they, too, can appreciate the cold frame as much as we do a

good sweater on a cold night.

*

* * 2008 * * *

The above

article was written many years (decades!) ago, but I'm still (2021) using the

same or similar cold frames. Some boxes have been replaced, some windows redone,

but they are still one of my most important gardening tools. The individual

boxes above work fine but some years ago I envisioned a larger, plot sized cold

frame for my tomatoes, with removable rack to hold semi-determinant plants

upright. Steve helped me design and build it and it has been great -- four eight

foot long cold frames, which fit my 4 ft x 32 ft plots. The last few years when

I didn't grow so many tomatoes they served well for peppers, and squash. They

are no longer fresh-wood-gold colored now but they still work great.

Copyright

© Susan Robishaw

INSET FRAMES: We made our first cold frame windows ourselves because we had

extra glass left over from building our house. Window glass is also readily

available in old windows whose frames are past use (or that had lead based paint

which you don’t want in your garden). Just remove the frames and use the

glass. Or look for good, used framed windows. Our homemade window frames are of

simple, overlapped corners design, made of pine.

INSET FRAMES: We made our first cold frame windows ourselves because we had

extra glass left over from building our house. Window glass is also readily

available in old windows whose frames are past use (or that had lead based paint

which you don’t want in your garden). Just remove the frames and use the

glass. Or look for good, used framed windows. Our homemade window frames are of

simple, overlapped corners design, made of pine.

TOP SET FRAMES -- Another simple design is the top-set frame, but with a slight

enhancement to keep the window from slipping off the back. We came up with this

second cold frame design when a friend gave us a batch of old aluminum clad

windows he’d replaced on a job. They were pretty flimsy compared to our

wood-framed windows, and not easy to attach a handle, so we made a box they

could sit on. This design can, of course, be used for any window that is flat on

the bottom, whether metal or wood framed.

TOP SET FRAMES -- Another simple design is the top-set frame, but with a slight

enhancement to keep the window from slipping off the back. We came up with this

second cold frame design when a friend gave us a batch of old aluminum clad

windows he’d replaced on a job. They were pretty flimsy compared to our

wood-framed windows, and not easy to attach a handle, so we made a box they

could sit on. This design can, of course, be used for any window that is flat on

the bottom, whether metal or wood framed.

CROPS IN THE COLD-FRAME -- Once you have a few cold frames, you’ll find many

uses for them throughout your garden. You will soon be scrounging up materials

to make more. In the late-summer and fall I start lettuce seedlings in a cold

frame box in the garden. As the weather gets cold and frosts and freezes arrive,

I add the window to protect them, propping it open on warm days. As the cold

settles in, half of the seedlings get transplanted to the greenhouse for late

fall and winter eating, the others continue to grow in the cold frame in the

garden. As the freezes end our regular lettuce crop, we eat the cold frame

protected plants until winter and deep snow arrives and our harvesting turns

inside to the greenhouse (where the plants are, hopefully, well along and

producing). In a milder climate this could continue throughout the winter, and

for other crops.

CROPS IN THE COLD-FRAME -- Once you have a few cold frames, you’ll find many

uses for them throughout your garden. You will soon be scrounging up materials

to make more. In the late-summer and fall I start lettuce seedlings in a cold

frame box in the garden. As the weather gets cold and frosts and freezes arrive,

I add the window to protect them, propping it open on warm days. As the cold

settles in, half of the seedlings get transplanted to the greenhouse for late

fall and winter eating, the others continue to grow in the cold frame in the

garden. As the freezes end our regular lettuce crop, we eat the cold frame

protected plants until winter and deep snow arrives and our harvesting turns

inside to the greenhouse (where the plants are, hopefully, well along and

producing). In a milder climate this could continue throughout the winter, and

for other crops.

In a good year (thankfully most years), as summer arrives and frosts abate, the

cold frames are removed from all of the plants. Four of the windows go on the

solar food dryer, while the rest are stored in the shed until needed in the

fall. The boxes are stacked out of the way not too far from the garden. If you

stack them up off the ground, kitty-corner to one another in the stack, they

will dry better and last longer. I’ve found old tires to be a good base, as

are used cement blocks.

In a good year (thankfully most years), as summer arrives and frosts abate, the

cold frames are removed from all of the plants. Four of the windows go on the

solar food dryer, while the rest are stored in the shed until needed in the

fall. The boxes are stacked out of the way not too far from the garden. If you

stack them up off the ground, kitty-corner to one another in the stack, they

will dry better and last longer. I’ve found old tires to be a good base, as

are used cement blocks.