The day after Thanksgiving in 1978 found us moving to our homestead in the

north, with much enthusiasm but little else. In particular, with no firewood

piled up to get us through the already accumulating snowy winter--and we planned

to heat and cook with wood.

Sometimes the only way to head into an adventure is spontaneously. It doesn’t

always end in disaster. We discovered we could build an adequate shelter with

few skills in record time. The every-day snow helped keep us on track And we

found we could get through even a record snow winter cutting our firewood “on

the hoof” every few days. It helped that we had a large supply of standing dead

elm fairly close by. For heating that is -- it didn’t help with the hauling.

What a year for learning -- including how to maneuver in the woods on snowshoes

with three feet of snow on the ground. And how NOT to haul firewood in deep

snow. We had an old box ice-fishing sled (wood sides, galvanized metal bottom,

no runners), and a kid’s round steel “saucer” sled. Both were good for their

intended purposes (sliding gear over ice, and providing a terrorizing ride down

a steep hill, respectively). But as firewood haulers, well, it was better than

carrying the load back to the cabin a few logs at a time in your arms, but not

much. In fact, I remember carrying a great amount of that year’s firewood supply

by hand (and arm).

We got through that winter, happily and healthily. But before the next snow

started falling, Steve had made a freight sled. We also had a decent supply of

firewood already stacked up, and have had since, more or less getting it in

before the snow flies. Just because something is a great adventure doesn’t mean

one has to (or wants to) repeat it. But that didn’t mean our winter hauling

needs were over. We still had the half mile through-the-woods,

over-hill-and-dale, and up-the-final-hill-to-the-car-and-road trek from November

to April.

You’d think by now that we would be sure to have everything we need on site

before winter sets in and we start walking (and hauling). By and large we do.

And we make good use of backpacks for the odds and ends that need to be carried

throughout the winter. But there is always the “special case”--the winter the

water table drops and we have to haul water from town until spring when we can

get more pipe down to extend the depth of the well pipe. Or that “good deal” on

a used drill press that came up in January (of course) and wouldn’t wait. Or

miscalculating the amount of chicken feed needed so we run out in February. Or

the woodworking idea that breaks upon one of us mid-winter that requires a

section of log from a tree that happens to be at the other end of the eighty. Or

an order for a box or two of books. Or an art fair in March. Or the hundred and

one other needs and desires that require sledding something heavy or awkward

over the snow.

THE FREIGHT SLED. In writing this article I realized the sled must be

over twenty years old now. A little worse for wear, yet it is still doing the

job. True, it doesn’t get as much use now. We have become better at planning and

being “ready for winter”. And it has a couple of co-worker-sleds now. But for

the heavy duty, gritty jobs, the old freight sled still comes out and does its

thing, with no more fuss or groaning than most of us who have been around for a

while.

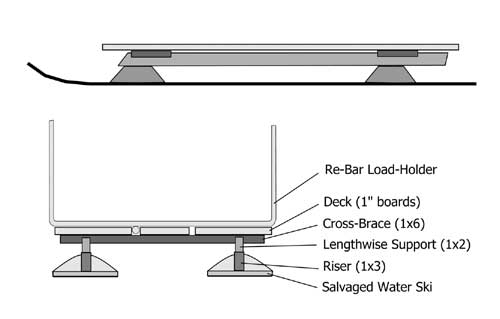

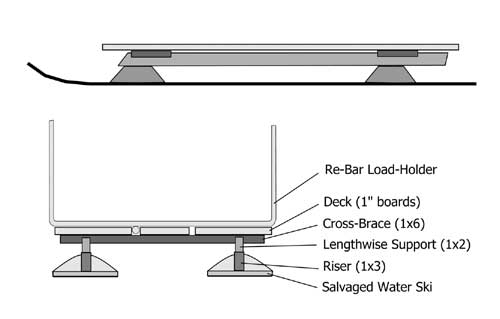

The

sled is based, literally and design wise, on a pair of old, wooden water skis,

found for sale in a place where one finds the old and used. Cheap as well as

sturdy, they were just what Steve was looking for. He cut the skis down to a

reasonable length (65 inches in this case), and built a sturdy wooden deck to

attach them to, using leftover pine boards from our cabin construction (see

photo and drawing). Holes drilled along the sides of the deck make it easy to

bungie the load down.

The

sled is based, literally and design wise, on a pair of old, wooden water skis,

found for sale in a place where one finds the old and used. Cheap as well as

sturdy, they were just what Steve was looking for. He cut the skis down to a

reasonable length (65 inches in this case), and built a sturdy wooden deck to

attach them to, using leftover pine boards from our cabin construction (see

photo and drawing). Holes drilled along the sides of the deck make it easy to

bungie the load down.

One of the first changes Steve made to the sled after a few runs was to add a

thin wooden “keel” to the bottom of the skis. Without this the sled tends to

make its own track--usually to one side then the other of the path you are

trying to stay on, which is irritating and tiring. This keel helps keep the sled

tracking behind you. It wears out and has to be replaced periodically, but it is

well worth the extra trouble.

The crowning touch, though, is the removable rebar rack. It is simply two pieces

of 5/8” rebar bent in flat 16 inch high U’s welded to a straight piece of rebar

with short ends bent down (see drawing). This piece fits in a space between the

deck boards, the bent ends fitting snuggly down over the cross braces beneath

the deck. Reinforced with small metal gussets brazed on over the welded points,

this makes a surprisingly sturdy rack. Two by two boards, drilled and slid over

the two U’s, help keep things from falling off. The arms of the U’s also help

keep the load on the sled, and give further attachment points for bungie or

rope. Over a flat path this wouldn’t be of much importance. But in the real

world, the ground, snow drifts, and path go up, down, this way, and that. Seldom

just flat. The sled tends to follow the contour. So does the load. You quickly

learn it’s easier to secure the load to begin with than to have to pick it up

and reload it along the way.

A simple rope handle ties to holes drilled in the front of the deck. Make sure

it is long enough to allow room for you and your snowshoes to fit in the space.

Heavy loads are much easier to pull with the rope around your waist than just

pulling it with your arms. And having the sled run over the backs of your

snowshoes gets old real fast. It should also then be long enough for two people

to pull when muscling the loaded sled up those steep parts.

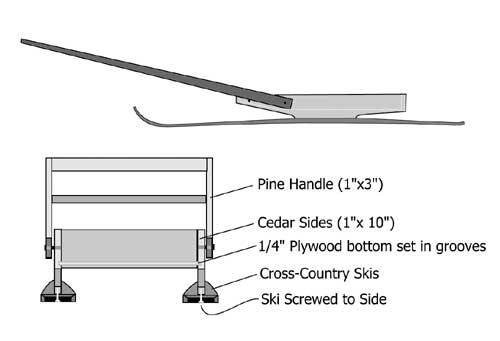

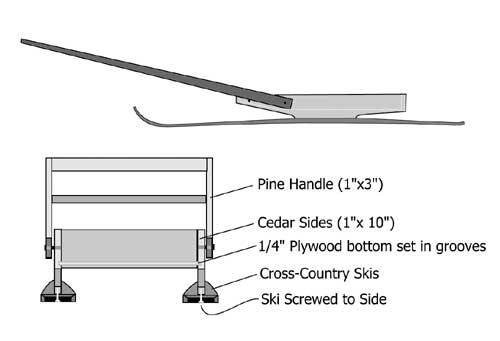

THE

GIFT SLED. My Christmas gifts from Steve are seldom conventional. Which is

fun. One year I received a wonderful, medium-weight hauling sled. As most of our

needs were no longer of the heavy and gritty type, we wanted something that

didn’t itself weigh a ton. (If you think that is an exaggeration, you have never

pulled a sled load of heavy boxes up a steep hill in wet snow). This sled

happily took over many of the sledding jobs, which were now usually up and down

the well packed half mile path from house to car. Based on a discarded pair of

cross country skis, it has a smaller but tighter deck, with short sides. A long

wooden handle replaces the rope handle of the freight sled. As the skis track

well and are seldom asked to carry the odd and heavy loads, the box has no tie

holes, though they would be easy to add if needed.

THE

GIFT SLED. My Christmas gifts from Steve are seldom conventional. Which is

fun. One year I received a wonderful, medium-weight hauling sled. As most of our

needs were no longer of the heavy and gritty type, we wanted something that

didn’t itself weigh a ton. (If you think that is an exaggeration, you have never

pulled a sled load of heavy boxes up a steep hill in wet snow). This sled

happily took over many of the sledding jobs, which were now usually up and down

the well packed half mile path from house to car. Based on a discarded pair of

cross country skis, it has a smaller but tighter deck, with short sides. A long

wooden handle replaces the rope handle of the freight sled. As the skis track

well and are seldom asked to carry the odd and heavy loads, the box has no tie

holes, though they would be easy to add if needed.

Nice refinements to the sled include short dowels in the front to keep the

handles from falling down into the snow. And the handle is fitted to allow it to

fold back over the sled body. Even without this, it is one long unit to store.

With the handle sticking out in front, it could be quite a problem. In the

winter it is parked in an aisle of the easily accessible woodshed. In the summer

it sometimes makes its way out of the woodshed and into another shed. By fall,

when we are usually filling the woodshed, it is stored in some out of the way

spot that is difficult to get to when the snow comes and you once again need the

sled.

The construction of this sled is fairly simple. The box sides extend down to be

also the base, with the skis attaching directly to them. The box bottom is 1/4

inch plywood, scarfed and bent up at a slight angle in the front to help direct

the snow under the sled. The plywood is let into a groove in the side pieces,

with a narrow board underneath in the middle for reinforcing. The wooden handle

is bolted to the sides of the box. When figuring the length needed for the

handle, use the person with the longest stride and longest snowshoes for

measuring. And remember, you will be walking, not standing still. This sled

works fine for me, but tends to clip the back of Steve’s snowshoes. Not enough

that we’ve bothered to lengthen the handle yet, just enough to be a minor

irritation.

The solid box of the sled makes it nice for carrying loads that you don’t want

to get snow covered and wet from melting snow. The slightly higher profile also

helps keep the load out of the snow, and the sides of the box help keep the load

secure. A simple tarp or plastic bag can be added if it is snowing when you are

hauling.

THE DESIGN and size of your own sled will depend on the materials you

have or can get. It will also depend on what you plan to carry, your ground, and

the snow conditions in your part of the country. But old skis are usually easily

found, and what has been built can be rebuilt and modified. (In fact, one of the

rules of the homestead that one tends to learn only later is that one should

always build with the idea that you will be taking it apart again someday.

Because you probably will.) So if you have need of a sled for hauling, go ahead,

collect some materials and build one. Or two. It can make life in snow country a

whole lot easier.

POSTSCRIPT. If we were to build another sled, what would we build now?

Well, several years ago friends gave us a light-weight cross-country skiing sled

they no longer were using. With a sturdy, smooth, plastic boat bottom; a

generous, zippered nylon top; and long, adjustable aluminum pole handles with a

padded waist belt and quick release buckle -- well, I admit, that is the

sled we most often use now. Not for firewood, or carving wood, or drill presses,

or a large load of boxes; but for the everyday hauling that we usually do in the

winter. If we didn’t have this one, the next sled built would probably be of a

similar idea. Light-weight wood frame with a covered body. A more aesthetically

pleasing version of the purchased plastic model. We’ve seen some nice ones made

for dog-sledders. It’s surprising how much weight they can carry. In fact, what

would be ideal (being the practical person that I am) would be a nice

lightweight body that could be put on ski’s for a sled in winter; then equipped

with wheels for a bicycle trailer in the summer. A wooden version, to go behind

the wooden recumbent bicycles Steve built for us.

Ah, the work of the homestead dreamer is never done.

* * * * * *

Copyright

© 2001 by Susan Robishaw and Stephen Schmeck

The

sled is based, literally and design wise, on a pair of old, wooden water skis,

found for sale in a place where one finds the old and used. Cheap as well as

sturdy, they were just what Steve was looking for. He cut the skis down to a

reasonable length (65 inches in this case), and built a sturdy wooden deck to

attach them to, using leftover pine boards from our cabin construction (see

photo and drawing). Holes drilled along the sides of the deck make it easy to

bungie the load down.

The

sled is based, literally and design wise, on a pair of old, wooden water skis,

found for sale in a place where one finds the old and used. Cheap as well as

sturdy, they were just what Steve was looking for. He cut the skis down to a

reasonable length (65 inches in this case), and built a sturdy wooden deck to

attach them to, using leftover pine boards from our cabin construction (see

photo and drawing). Holes drilled along the sides of the deck make it easy to

bungie the load down.

THE

GIFT SLED. My Christmas gifts from Steve are seldom conventional. Which is

fun. One year I received a wonderful, medium-weight hauling sled. As most of our

needs were no longer of the heavy and gritty type, we wanted something that

didn’t itself weigh a ton. (If you think that is an exaggeration, you have never

pulled a sled load of heavy boxes up a steep hill in wet snow). This sled

happily took over many of the sledding jobs, which were now usually up and down

the well packed half mile path from house to car. Based on a discarded pair of

cross country skis, it has a smaller but tighter deck, with short sides. A long

wooden handle replaces the rope handle of the freight sled. As the skis track

well and are seldom asked to carry the odd and heavy loads, the box has no tie

holes, though they would be easy to add if needed.

THE

GIFT SLED. My Christmas gifts from Steve are seldom conventional. Which is

fun. One year I received a wonderful, medium-weight hauling sled. As most of our

needs were no longer of the heavy and gritty type, we wanted something that

didn’t itself weigh a ton. (If you think that is an exaggeration, you have never

pulled a sled load of heavy boxes up a steep hill in wet snow). This sled

happily took over many of the sledding jobs, which were now usually up and down

the well packed half mile path from house to car. Based on a discarded pair of

cross country skis, it has a smaller but tighter deck, with short sides. A long

wooden handle replaces the rope handle of the freight sled. As the skis track

well and are seldom asked to carry the odd and heavy loads, the box has no tie

holes, though they would be easy to add if needed.